The prolonged boom that we’ve experienced in the technology field for the past decade — what some have called the second dot-com boom and which is intrinsically tied to the rise of big data and AI — is now coming to a close, according to some industry-watchers. However, predictions like this have been made before, and not everybody is ready to write off the current wave of expansion.

A series of layoffs at technology-backed startups has the pessimists predicting poor forward-looking results. Uber laid off over 400 folks late last year, while its competitor Lyft gave pink slips to nearly 100 workers. Lime, Mozilla, 23andMe, and Quora have also let people go. WeWork had a disastrous fourth quarter that cost the company 80% of its valuation, its planned IPO, and the CEO his job.

All told, at least 30 startups have laid off 8,000 employees over the past four months, according to a tally by the New York Times. “It feels like a reckoning is here,” Josh Wolfe, a venture capitalist at Lux Capital in New York, told the newspaper in an article last month.

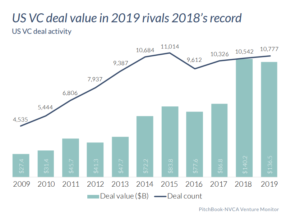

From 2009 to 2019, startups raised more than $790 billion across angel, early-round, and late-stage deals, according to data accumulated by PitchBook and the National Venture Capital Association in their Venture Monitor report for the fourth quarter of 2019, which was published in January 2020.

Lime has left San Diego and 11 other cities as it scales back activities (Simone Hogan/Shutterstock)

A good fraction of this money was funneled into firms with new business models in fields like delivery, cannabis, real estate, and direct-to-consumer goods, according to the Times. These firms sought to utilize the latest technology, including advanced analytics and AI, to disrupt established firms, and some did quite well at it.

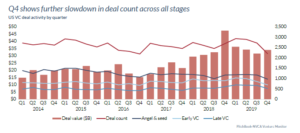

But the stream of money is showing signs of slowing down, which has some VCs worried. The last three months of 2019 saw the fewest number of rounds of financing for startups since late 2016, according to the NVCA and PitchBook report. When you combine the recent slowdown in VC money with the layoffs in tech-focused startups, it starts people talking.

That fear is starting to creep into the business models. When the sentiment is generally positive and expansion is assumed, then executives at startups focus on establishing a beachhead and accumulating users. But as sentiment droops a bit, the focus is shifting and now there’s a greater focus on being profitable, according to the Times. The new CEO for Lime, for example, says being profitable is the company’s main goal now.

VCs are accustomed to backing technology firms that lose money, but only if the potential upside in the long-run is so great that they can justify losing money in the short-run. We have seen this dynamic play out in the big data industry, particularly with the Hadoop distributors, which lost tens of millions of dollars for years as they established customer bases.

The number of VC deals decreased steadily for the last three quarters in 2019 (Source: Venture Monitor 4Q19 report)

But as we saw in early 2019, when both MapR Technologies (now part of HPE) and Cloudera ran into trouble following poor sales results, investors will not tolerate an endless expanse of red ink. What’s more, their sentiment can turn on a dime. The remnants of the popping of the Hadoop hype bubble is still resonating across the big data market (if there is such a thing), and technology execs should heed the lessons learned.

A Positive Outlook

While the gusher of VC money is slowing down, that doesn’t automatically indicate dark times ahead. Some have a positive outlook, including Bobby Franklin, the CEO and president of NVCA.

“The big question mark at the start of 2019 was how VC deal value would fare after a historic showing in the year prior,” Franklin states in the introduction to Pitchbook’s Venture Monitor report for the fourth quarter of 2019.

The total value of VC investment in 2019 was close to the all-time high from 2018 (Source: Venture Monitor 4Q19 report)

“Some thought that 2018 was a peak and the VC industry would start slowing down, while others believed that this substantial level of investment presented the new normal,” he continues. “Now that we’ve closed the books on 2019, the latter seems increasingly possible due to a variety of structural changes within VC, with deal activity maintaining the record levels seen in 2018.”

Franklin wrote that before Mother Nature dealt us a wildcard in the form of novel coronavirus, a highly contagious disease which is now spreading globally. The virus is wreaking havoc on public health at the moment, and the stock market has responded accordingly. The Dow Jones Industrial Average was down more than 10% last week on fears that a protracted outbreak could suppress economic activity for months. That’s correction-level territory, and it could change the level of risk that investors are willing to take in their pursuit of profits through tech-focused investments.

The market correction has lopped trillions of dollars of market capitalization off publicly traded companies. The three cloud giants, which collectively are worth more than $3.1 trillion, have lost over $300 billion in market cap, with Microsoft losing 10% and Amazon and Google both losing 13% of valuation from their recent highs in mid -February, leaving Microsoft (and Apple, which has its own supply chain problems for the iPhone) as the only tech firms currently worth more than $1 trillion.

Some VCs are bullish that continued technological innovation will provide investment opportunities for years to come

It’s definitely possible that the current tech boom — which has coincided with the largest period of continued growth in United States history – could be coming to a close. From a macro-economic point of view, the spread of the coronavirus does not appear to be leveling off, and hundreds of conferences have already been canceled, which will have a negative impact on the cities that host conferences. In the tech industry, almost every major conference scheduled for the next two months has been canceled or turned into a virtual event. That will put a damper on the market activities of the companies that develop the data management and AI tools.

However, in the long run, it seems like there is a very good chance that elements of the tech boom will continue. Theirs is little to no chance that the forces of innovation that the big data and AI revolution have been unleashed on the world will be put back into the bottle. Unless people and things stop generating data, there is too much value in analyzing that data to improve some aspect of a business or an organization.

In the PitchBook report, Greg Becker, the president and CEO of Silicon Valley Bank (a sponsor of the report), says the “innovation economy” is booming across all sectors at the moment, and that technology-driven innovation will continue to deliver dividends for investors and businesses in the coming months.

“If a company or industry isn’t innovating today, by almost any definition, it is dying,” Becker says in a Q&A in Pitchbook’s fourth-quarter report. “Every sector is turning to tech to compete and stay relevant.”

Innovation is not decelerating, for a number of reasons. “First, it’s cheaper,” he says. “The cost of enabling technologies—including AI, data analytics and storage capacity—continues to drop. The first whole human genome sequencing cost $2.7 billion 15 years ago. Today, the cost is less than $1,000.”

While some states saw a drop in the number of tech jobs, overall the tech industry created 261,000 jobs in 2018, for a total of 11.5 million jobs, which contributed $1.6 trillion to the country’s economy. With thousands of openings for hard-to-fill jobs, like data engineer, machine learning specialist, and data scientist, it’s clear that companies across all sectors are struggling to keep up in the data innovation department.

In our little section of the market, executives tell Datanami that they expect some consolidation to happen. We may be passed the period of rapid innovation that occurred from 2013 to 2016, when new software startups and data projects flourished. We have seen dozens, if not hundreds, of startups snapped up by bigger firms with healthier balance sheets.

That consolidation process will likely continue as executives become less accepting of losses. But it also won’t prevent data innovators from taking their good ideas and starting new companies with them. That creative process will continue as the wave of data-driven innovation that has already been unleashed continues to ripple across all industries, a process that will likely play out for years, if not decades, to come.

This article originally appeared on Datanami.